David Lynch’s films are exercises in transgression, where nothing is off-limits. Each of his works stands as a rebellious entity, defying conventional narrative structures. Fragmentation and storylines that spiral unpredictably are natural elements in the Lynchian universe. In this world, anything can happen, and it often does. Lynch delves into the unknowable, exploring the latent horrors lurking beneath the facade of normalcy. His 1986 masterpiece, Blue Velvet, remains a striking critique of the American Dream, piercing through its polished exterior. Beneath the veneer of uniformity and standardized ideals lies a dark underbelly of repression and despair. Lynch’s cinema exposes this hollowness at the heart of suburban life, revealing corrupt masculinity and societal toxicity in a stark, often graphic manner. As renowned critic Pauline Kael observed, Lynch’s films bring mystery and madness into the realm of the everyday.

Countless films have since attempted to replicate Lynch’s style, often teetering into parody, but none have matched the raw, dissonant fusion of sex, grotesquerie, and violence in small-town America that Blue Velvet achieved. Lynch’s films are chaotic yet deeply emotional, refusing to conform to a single emotional or narrative plane. His characters and stories traverse multiple identities and timelines, shifting seamlessly between past, present, and future. In his sprawling three-hour opus, Inland Empire (2006), disjointed scenes—such as one involving a prostitute entering a hotel room and another showing a bleeding figure, played by entirely different actors—highlight his mastery of irrational connections. Kael aptly noted, “Lynch’s use of irrational material works the way it’s supposed to: we read his images at some not fully conscious level.”

Lynch’s visual language often transcends logic, drifting into the surreal. For instance, Inland Empire features life-sized rabbits in suits, a striking example of his bizarre dreamlike imagery. His characters frequently display hints of psychological disorders, always seeking an escape from the confines of reality. This rejection of expectations plunges his narratives into a nightmarish, half-conscious state. In Mulholland Drive (2001), Hollywood’s illusions are laid bare, depicting a world where characters’ efforts to control their destinies unravel into chaos. Dreams are warped and perverted, with characters and scenes transforming into unrecognizable versions of themselves. While Lynch’s films may appear to occupy alternate realities, they often reveal that the decay resides within, not outside.

Lynch’s work is provocative and polarizing. As one of the first auteurs to make a significant impact on television, his ABC drama Twin Peaks transformed Laura Palmer’s murder mystery into a bold exploration of Americana, blending melodrama and suspense. Beauty and terror coexist seamlessly in Lynch’s storytelling. He never confined himself to traditional genre boundaries, moving fluidly between noir, soap opera, and horror. Familiar settings in his films are disrupted by surreal and shocking moments, such as the infamous monster appearing behind the diner in Mulholland Drive.

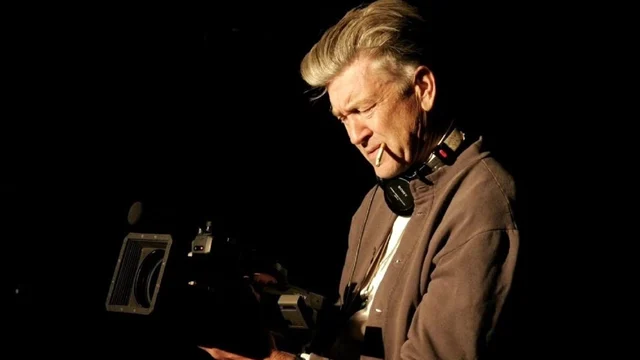

Known for his resistance to conventional interpretation, Lynch often dismissed efforts to extract intentional meaning from his work. His inscrutability adds to the allure of his creations. As he explained in an interview with critic Adam Nayman: “A thing is what it is, and that’s what it wants to be.”